In this article, you will learn how Python allocates, tracks, and reclaims memory using reference counting and generational garbage collection, and how to inspect this behavior with the gc module.

Topics we will cover include:

- The role of references and how Python’s reference counts change in common scenarios.

- Why circular references cause leaks under pure reference counting, and how cycles are collected.

- Practical use of the

gcmodule to observe thresholds, counts, and collection.

Let’s get right to it.

Everything You Need to Know About How Python Manages Memory

Image by Editor

Introduction

In languages like C, you manually allocate and free memory. Forget to free memory and you have a leak. Free it twice and your program crashes. Python handles this complexity for you through automatic garbage collection. You create objects, use them, and when they’re no longer needed, Python cleans them up.

But “automatic” doesn’t mean “magic.” Understanding how Python’s garbage collector works helps you write more efficient code, debug memory leaks, and optimize performance-critical applications. In this article, we’ll explore reference counting, generational garbage collection, and how to work with Python’s gc module. Here’s what you’ll learn:

- What references are, and how reference counting works in Python

- What circular references are and why they’re problematic

- Python’s generational garbage collection

- Using the

gcmodule to inspect and control collection

Let’s get to it.

What Are References in Python?

Before we move to garbage collection, we need to understand what “references” actually are.

When you write this:

Here’s what actually happens:

- Python creates an integer object 123 somewhere in memory

- The variable

xstores a pointer to that object’s memory location xdoesn’t “contain” the integer value — it points to it

So in Python, variables are labels, not boxes. Variables don’t hold values; they’re names that point to objects in memory. Think of objects as balloons floating in memory, and variables as strings tied to those balloons. Multiple strings can be tied to the same balloon.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

# Create an object my_list = [1, 2, 3] # my_list points to a list object in memory

# Create another reference to the SAME object another_name = my_list # another_name points to the same list

# They both point to the same object print(my_list is another_name) print(id(my_list) == id(another_name))

# Modifying through one affects the other (same object!) my_list.append(4) print(another_name)

# But reassigning creates a NEW reference my_list = [5, 6, 7] # my_list now points to a DIFFERENT object print(another_name) |

When you write another_name = my_list, you’re not copying the list. You’re creating another pointer to the same object. Both variables reference (point to) the same list in memory. That’s why changes through one variable appear in the other. So the above code will give you the following output:

|

True True [1, 2, 3, 4] [1, 2, 3, 4] |

The id() function shows the memory address of an object. When two variables have the same id(), they reference the same object.

Okay, But What Is a “Circular” Reference?

A circular reference occurs when objects reference each other, forming a cycle. Here’s a super simple example:

|

class Person: def __init__(self, name): self.name = name self.friend = None # Will store a reference to another Person

# Create two people alice = Person(“Alice”) bob = Person(“Bob”)

# Make them friends – this creates a circular reference alice.friend = bob # Alice’s object points to Bob’s object bob.friend = alice # Bob’s object points to Alice’s object |

Now we have a cycle: alice → Person(“Alice”) → .friend → Person(“Bob”) → .friend → Person(“Alice”) → …

Here’s why it’s called “circular” (in case you haven’t guessed yet). If you follow the references, you go in a circle: Alice’s object references Bob’s object, which references Alice’s object, which references Bob’s object… forever. It’s a loop.

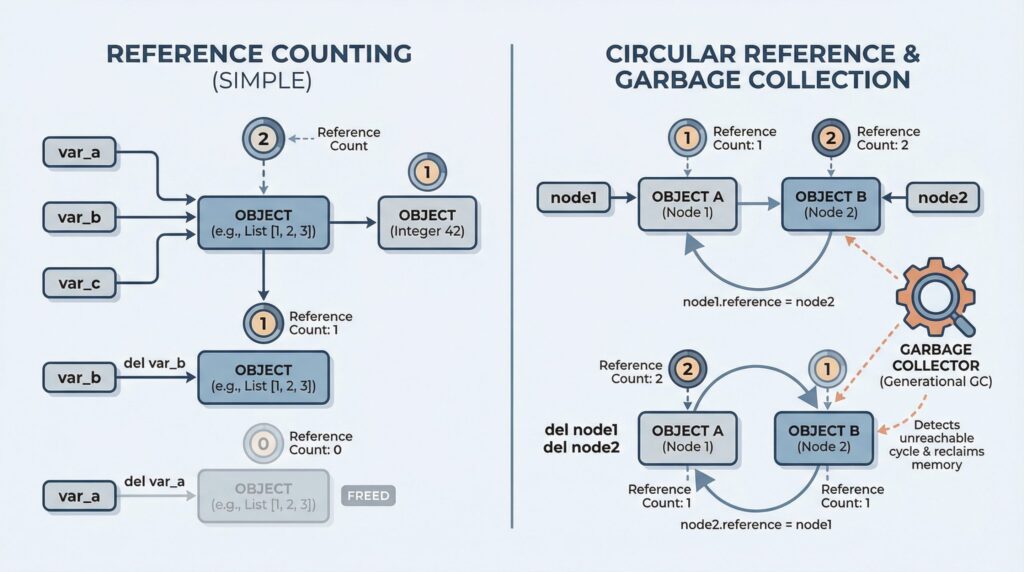

How Python Manages Memory Using Reference Counting & Generational Garbage Collection

Python uses two main mechanisms for garbage collection:

- Reference counting: This is the primary method. Objects are deleted when their reference count reaches zero.

- Generational garbage collection: A backup system that finds and cleans up circular references that reference counting can’t handle.

Let’s explore both in detail.

How Reference Counting Works

Every Python object has a reference count which is the number of references to it, meaning variables (or other objects) pointing to it. When the reference count reaches zero, the memory is immediately freed.

|

import sys

# Create an object – reference count is 1 my_list = [1, 2, 3] print(f“Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Create another reference – count increases another_ref = my_list print(f“Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete one reference – count decreases del another_ref print(f“Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete the last reference – object is destroyed del my_list |

Output:

|

Reference count: 2 Reference count: 3 Reference count: 2 |

Here’s how reference counting works. Python keeps a counter on every object tracking how many references point to it. Each time you:

- Assign the object to a variable → count increases

- Pass it to a function → count increases temporarily

- Store it in a container → count increases

- Delete a reference → count decreases

When the count hits zero (no references left), Python immediately frees the memory.

📑 About

sys.getrefcount(): The count shown bysys.getrefcount()is always 1 higher than you expect because passing the object to the function creates a temporary reference. If you see “2”, there’s really only 1 external reference.

Example: Reference Counting in Action

Let’s see reference counting in action with a custom class that announces when it’s deleted.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

class DataObject: “”“Object that announces when it’s created and destroyed”“”

def __init__(self, name): self.name = name print(f“Created {self.name}”)

def __del__(self): “”“Called when object is about to be destroyed”“” print(f“Deleting {self.name}”)

# Create and immediately lose reference print(“Creating object 1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 1”)

print(“\nCreating object 2 and deleting it:”) obj2 = DataObject(“Object 2”) del obj2

print(“\nReassigning obj1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 3”)

print(“\nFunction scope test:”) def create_temporary(): temp = DataObject(“Temporary”) print(“Inside function”)

create_temporary() print(“After function”)

print(“\nScript ending…”) |

Here, the __del__ method (destructor) is called when an object’s reference count reaches zero. With reference counting, this happens immediately.

Output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

Creating object 1: Created Object 1

Creating object 2 and deleting it: Created Object 2 Deleting Object 2

Reassigning obj1: Created Object 3 Deleting Object 1

Function scope test: Created Temporary Inside function Deleting Temporary After function

Script ending... Deleting Object 3 |

Notice that Temporary is deleted as soon as the function exits because the local variable temp goes out of scope. When temp disappears, there are no more references to the object, so it’s immediately freed.

How Python Handles Circular References

If you’ve followed along carefully, you’ll see that reference counting can’t handle circular references. Let’s see why.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

import gc import sys

class Node: def __init__(self, name): self.name = name self.reference = None

def __del__(self): print(f“Deleting {self.name}”)

# Create two separate objects print(“Creating two nodes:”) node1 = Node(“Node 1”) node2 = Node(“Node 2”)

# Now create the circular reference print(“\nCreating circular reference:”) node1.reference = node2 node2.reference = node1

print(f“Node 1 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node1) – 1}”) print(f“Node 2 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node2) – 1}”)

# Delete our variables print(“\nDeleting our variables:”) del node1 del node2

print(“Objects still alive! (reference counts aren’t zero)”) print(“They only reference each other, but counts are still 1 each”) |

When you try to delete these objects, reference counting alone can’t clean them up because they keep each other alive. Even if no external variables reference them, they still have references from each other. So their reference count never reaches zero.

Output:

|

Creating two nodes:

Creating circular reference: Node 1 refcount: 2 Node 2 refcount: 2

Deleting our variables: Objects still alive! (reference counts aren‘t zero) They only reference each other, but counts are still 1 each |

Here’s a detailed analysis of why reference counting won’t work here:

- After we delete

node1andnode2variables, the objects still exist in memory - Node 1’s object has a reference (from Node 2’s

.referenceattribute) - Node 2’s object has a reference (from Node 1’s

.referenceattribute) - Each object’s reference count is 1 (not 0), so they aren’t freed

- But no code can reach these objects anymore! They’re garbage, but reference counting can’t detect it.

This is why Python needs a second garbage collection mechanism to find and clean up these cycles. Here’s how you can manually trigger garbage collection to find the cycle and delete the objects like so:

|

print(“\nTriggering garbage collection:”) collected = gc.collect() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”) |

This outputs:

|

Triggering garbage collection: Deleting Node 1 Deleting Node 2 Collected 2 objects |

Using Python’s gc Module to Inspect Collection

The gc module lets you control and inspect Python’s garbage collector:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 |

import gc

# Check if automatic collection is enabled print(f“GC enabled: {gc.isenabled()}”)

# Get collection thresholds thresholds = gc.get_threshold() print(f“\nCollection thresholds: {thresholds}”) print(f” Generation 0 threshold: {thresholds[0]} objects”) print(f” Generation 1 threshold: {thresholds[1]} collections”) print(f” Generation 2 threshold: {thresholds[2]} collections”)

# Get current collection counts counts = gc.get_count() print(f“\nCurrent counts: {counts}”) print(f” Gen 0: {counts[0]} objects”) print(f” Gen 1: {counts[1]} collections since last Gen 1″) print(f” Gen 2: {counts[2]} collections since last Gen 2″)

# Manually trigger collection and see what was collected print(f“\nCollecting garbage…”) collected = gc.collect() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”)

# Get list of all tracked objects all_objects = gc.get_objects() print(f“\nTotal tracked objects: {len(all_objects)}”) |

Python uses three “generations” for garbage collection.

- New objects start in generation 0.

- Objects that survive a collection are promoted to generation 1, and eventually generation 2.

The idea is that objects that have lived longer are less likely to be garbage.

When you run the above code, you should see something like this:

|

GC enabled: True

Collection thresholds: (700, 10, 10) Generation 0 threshold: 700 objects Generation 1 threshold: 10 collections Generation 2 threshold: 10 collections

Current counts: (423, 3, 1) Gen 0: 423 objects Gen 1: 3 collections since last Gen 1 Gen 2: 1 collections since last Gen 2

Collecting garbage... Collected 0 objects

Total tracked objects: 8542 |

The thresholds determine when each generation is collected. When generation 0 has 700 objects, a collection is triggered. After 10 generation 0 collections, generation 1 is collected. After 10 generation 1 collections, generation 2 is collected.

Conclusion

Python’s garbage collection combines reference counting for immediate cleanup with cyclic garbage collection for circular references. Here are the key takeaways:

- Variables are pointers to objects, not containers holding values.

- Reference counting tracks how many pointers point to each object. Objects are freed immediately when reference count reaches zero.

- Circular references happen when objects point to each other in a cycle. Reference counting can’t handle circular references (counts never reach zero).

- Generational garbage collection finds and cleans up circular references. There are three generations: 0 (young), 1, 2 (old).

- Use

gc.collect()to manually trigger collection.

Understanding that variables are pointers (not containers) and knowing what circular references are helps you write better code and debug memory issues.

I said “Everything you Need to Know…” in the title, I know. But there’s more (there always is) you can learn such as how weak references work. A weak reference allows you to refer to or point to an object without increasing its reference count. Sure, such references add more complexity to the picture but understanding weak references and debugging memory leaks in your Python code are a few next steps worth exploring for curious readers. Happy exploring!