PVC window frames rely on a metal scaffold for stability. But what if another strong material with lower heat conductivity was used in place of the metal? This would improve the overall thermal insulation of the window and its energy efficiency, making homes warmer and friendlier to the environment. A common manufacturing technique that could produce such alternative scaffold elements has been tested and refined in a study by Skoltech researchers, published in Materials & Design.

In the paper, the team reports manufacturing thermoplastic composite profiles—rectangular pipes made of plastic reinforced with glass fiber—using a technology called pultrusion. It involves pulling commercially available tapes made of glass fiber infused with polypropylene through a machine that heats and fuses them together in a narrow space. The resulting long part shaped as a board, plank, or beam is called a profile.

The study reveals previously unknown details of the production process that will help manufacturers avoid excessive power consumption and defects in the end product. “You see, while we understand well how so-called thermosetting polymers behave during pultrusion, this is not the case for thermoplastic polymers, such as the polypropylene in this study. But pultrusion could make much sense with those polymers, too,” said Associate Professor Alexander Safonov of Skoltech Materials, the project’s principal investigator.

Unlike thermosetting polymers, their thermoplastic counterparts can be repeatedly melted and consolidated. For a PVC window frame scaffold made of fiber-reinforced polymer parts this has a number of advantages, Safonov explains, “They can be welded. They are recyclable. Their manufacture releases no harmful volatile organic compounds into the environment. Also, the source materials—that is, tapes—are convenient because of their very long shelf life.”

These considerations led the Skoltech researchers to experiment with the pultrusion of composite profiles made of glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene.

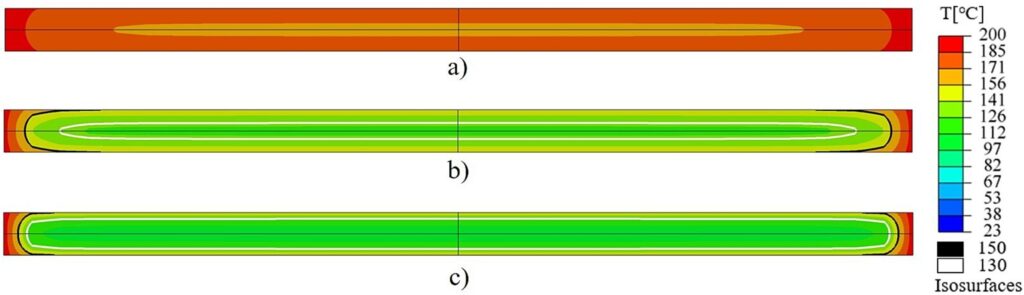

“In the die, the tapes are heated from below and from above, and if you imagine a cross section of a rectangular profile manufactured by this process, we did not know how the temperature is distributed throughout it. And this is important, because if some part of the profile does not get enough heat, the product will be defective. Also, we wanted to see just how much heat is really needed for the profile to consolidate, because if you crank up the heat every time just to make sure, you will face unnecessary utility costs,” said the study’s lead author Kirill Minchenkov, a Ph.D. student at Skoltech Materials.

The team relied on a temperature sensor known as a thermocouple to measure how the temperature at one point in the cross section varies as the profile undergoes heating and subsequent cooling in the pultrusion process.

The thermocouple is in essence two coupled wires made of different alloys. In such an arrangement, their electrical conductivity varies in a highly predictable way based on ambient temperature. So by pulling the thermocouple along with the tapes through the die, the researchers could monitor the local temperature of the material at any given time.

These measurement data were obtained for various speeds at which the tapes may be pulled through the machine, from 3.3 millimeters per second to four times as fast. Knowing the thermal conductivity of the material and the temperature evolution close to the center of the profile, which was observed in the experiment, the researchers created a geometric model of the heated and the cooling dies and calculated the temperature distribution for the entire cross section.

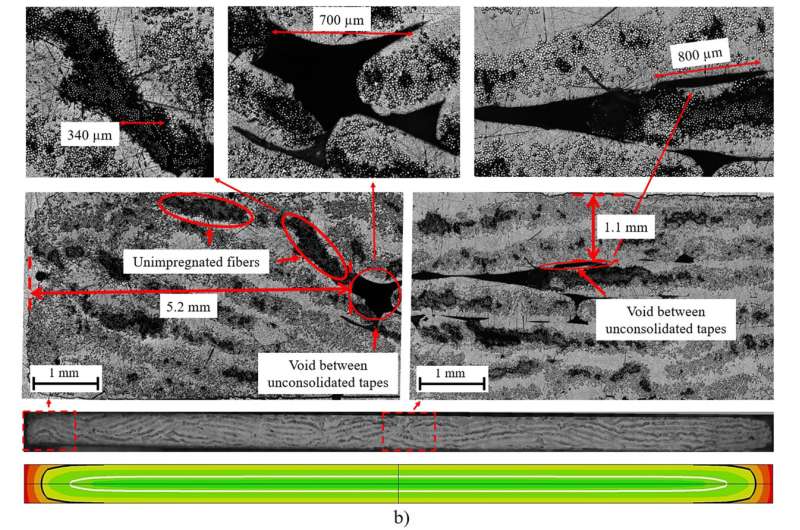

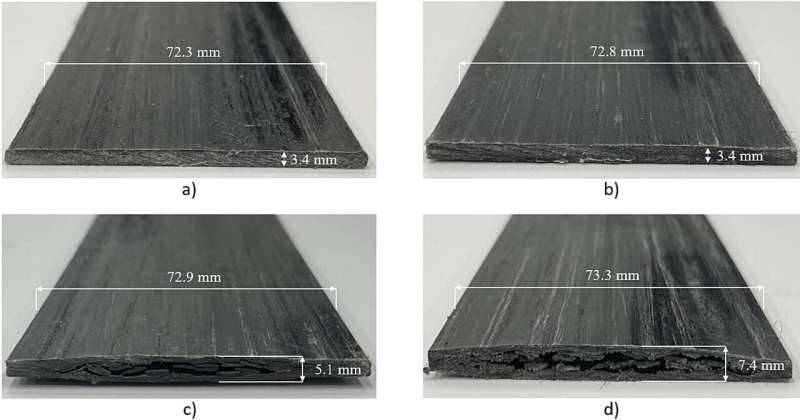

Having obtained these temperature distributions, the team also studied the profiles manufactured at different pulling speeds with an optical microscope and subjected them to mechanical strength tests. Of those tested, only the slowest pulling speed proved suitable for manufacturing high-quality profiles, as evidenced by microscopy and mechanical tests.

Interestingly, upon close examination of profile microphotographs from scenario (b), the researchers found that the defects either fell within the central area enclosed by the white contour in the temperature map, or else they had a different nature and stemmed from imperfections in the raw materials (namely, fibers not impregnated with polymer in the tapes), rather than from the pultrusion process.

As it turns out, the cold central zone harboring defects not only hadn’t reached the melting point of polypropylene but in fact hadn’t even reached the somewhat lower Vicat softening temperature. In areas that did pass this threshold temperature, the material consolidated as needed even below the melting point.

“We therefore conclude that it is possible to conserve power and save on utility costs by heating the tapes to the Vicat temperature, unless the manufacturer has reason to doubt the quality of the source materials. If, however, the preconsolidated tapes contain defects in the form of pores, heating them past the Vicat temperature and to the melting point is the better option to get rid of those defects,” Minchenkov said.

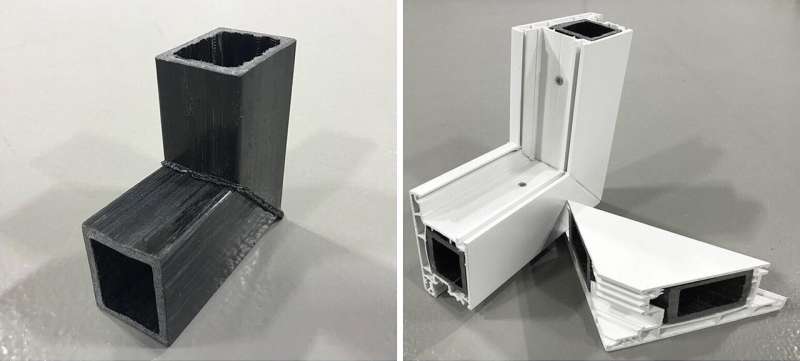

After doing the experiments, modeling, and mechanical tests on flat profiles, the team manufactured a square hollow tube of the same material to demonstrate applicability in PVC window frames.

Asked about the latest developments on the project and the team’s future plans, study co-author Senior Engineer Sergey Gusev of Skoltech Materials, who was in charge of sample manufacturing, commented, “In this study we only investigated glass fiber-reinforced composites with polypropylene as the polymer matrix. But we are exploring other materials, too. Right now, we are experimenting with carbon and basalt fibers, and with polyamide and polyphenylene sulfide matrices.”

“This may give the pultruded profiles an additional edge for applications in construction—in PVC windows and beyond.”

More information:

Kirill Minchenkov et al, Experimental and numerical analyses of the thermoplastic pultrusion of large structural profiles, Materials & Design (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112149

Citation:

Study explores ways to make PVC windows warmer and add recyclable components (2023, October 12)

retrieved 13 October 2023

from https://techxplore.com/news/2023-10-explores-ways-pvc-windows-warmer.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.