A last gasp in a long-standing link between Russia and Ukraine in the field of rocketry could come this week in an unlikely place—the rural wetlands of eastern Virginia—halfway around the world from the battlefields where the nations’ military forces are locked in a deadly conflict.

A commercial Antares rocket owned by the US aerospace and defense contractor Northrop Grumman is set for launch from Wallops Island, Virginia, as soon as Tuesday evening hauling an automated Cygnus supply ship into orbit on a mission to the International Space Station. When it takes off, the Antares rocket will be powered by two Russian-made engines affixed to the bottom of a first-stage booster built in Ukraine.

This is how Northrop Grumman has launched most of its 19 resupply missions to the space station since 2013, but this week’s mission will be the last Antares flight to use Russian and Ukrainian components. Northrop Grumman has partnered with Firefly Aerospace, which has already built and launched a small satellite launcher of its own, to develop a new US-built first stage to replace the Ukrainian booster. Firefly will supply seven of its own engines, called the Miranda, to propel each of the new-generation Antares rockets into space.

Sanctions introduced after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 severed most ties between Western companies and Russian industry, not to mention the deteriorating political support for such partnerships. It strained the relationship between the United States and Russia on the ISS, but for now, that program appears poised to continue flying through at least 2030.

Northrop Grumman lost access to the Russian RD-181 engines it was importing from a Moscow-area company called Energomash, one of Russia’s pre-eminent rocket engine manufacturers. And the effects of the fighting in Ukraine threatened to interrupt the production of new Antares rocket bodies at a factory operated by Yuzhmash in Dnipro. The factory itself has been the target of Russian missile strikes.

A long history

Russia and Ukraine have partnered on rocket programs since the dawn of the Space Age when they were parts of the Soviet Union. Factories in Ukraine produced ballistic missiles designed for Soviet nuclear attacks on the United States, and Ukraine churned out parts that went into rockets and satellites assembled in Russia.

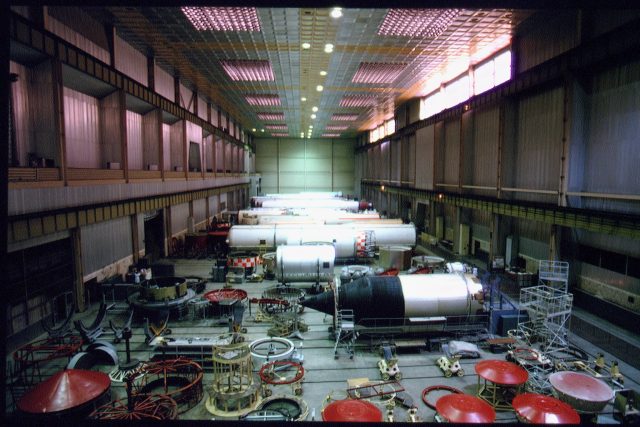

When it started designing the Antares cargo rocket in the late 2000s, Orbital Sciences—a commercial space company now absorbed into Northrop Grumman—saw ready-made partners in Russia and Ukraine. Orbital Sciences went with two Ukrainian companies, Yuzhnoye and Yuzhmash, to build Antares boosters based on a design already used by the Zenit rocket, which had been flying since the 1980s with a mix of Ukrainian and Russian technology.

For the main propulsion system, Orbital Sciences decided on leftover NK-33 rocket engines from the Soviet N1 Moon rocket. That turned out to be a mistake, a lesson learned in 2014 when an engine failure caused an Antares rocket to explode just seconds after liftoff, destroying the Cygnus cargo freighter bound for the space station.

Engineers redesigned the rocket to use newly manufactured RD-181 engines from Russia’s Energomash and launched three Cygnus resupply flights to the station with United Launch Alliance Atlas V rockets. The retrofitted Antares rocket configuration, the Antares 230, started flying in 2016 and has logged 12 successful launches in a row.

But those successes came as Russian-Ukrainian relations frayed. The last launch of a Zenit rocket, upon which the Antares design is based, occurred in 2017.

About a year ago, months after the Russian-Ukrainian conflict erupted into a hot war, Northrop Grumman announced it would design and develop an all-American Antares rocket with Firefly that could be ready to fly by the end of 2024. The company calls the version of the Antares rocket to be retired with this week’s launch the Antares 230+, while the new variant with Firefly’s booster stage will be named the Antares 330.

Kurt Eberly, Northrop Grumman’s director of space launch programs, said Sunday that the Antares 330 rocket is now expected to launch no sooner than mid-2025. Until then, Northrop has purchased three Falcon 9 launches with SpaceX to continue flying Cygnus cargo ships to the space station at a rate of about twice per year. The first of the Cygnus cargo missions to fly on a Falcon 9 is scheduled to take off in December from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

SpaceX and Northrop Grumman each have multibillion-dollar contracts with NASA to deliver supplies and experiments to the space station. Unlike Northrop’s Cygnus, SpaceX’s Dragon cargo capsule can return equipment and scientific specimens to Earth.

“The first and foremost mission goal we have is to support the needs of the space station and the astronauts, so certainly when we have to pivot to a new launch vehicle… we’re more than happy to do that,” said Steve Krein, Northrop Grumman’s vice president of civil and commercial space programs. “We collaborate with our competitors all the time, and we’re certainly doing that with SpaceX here.”

Under the terms of its firm-fixed price contractual arrangement with NASA, Northrop Grumman is on the hook for any extra expenses to carry out its cargo missions. In addition to paying the base price for a SpaceX launch, Krein said Northrop is paying for some modifications to the Falcon 9’s payload fairing to accommodate the Cygnus spacecraft (presumably for late cargo loading), along with upgrades to ground facilities at Cape Canaveral. SpaceX’s Dragon cargo flights do not use a payload fairing.

After flying the next three Cygnus resupply flights on SpaceX rockets, Northrop Grumman hopes the upgraded Antares 330 rocket will be ready for service. The current plan is to fly an operational Cygnus resupply mission on the inaugural flight of the Antares 330, but a lot of work remains to be completed on Firefly’s Miranda engine, which hasn’t been test-fired at full scale. Eberly said a Miranda test firing is scheduled to happen this fall.

Working in Northrop Grumman’s favor is the fact that the Antares 330 design will incorporate the same solid-fueled upper-stage motor as the current Antares rocket configuration. That upper stage is built in-house by Northrop Grumman.

The new Antares 330 rocket will be able to loft heavier payloads into orbit, nearly 30 percent more than the soon-to-be-retired Antares 230 rocket. Ultimately, Northrop and Firefly want to evolve the Antares rocket into a still-unnamed medium-lift launch vehicle with a more powerful upper stage. The goal is to field a launch vehicle that can compete for military and commercial launch contracts with medium to large rockets being developed by Relativity Space and Rocket Lab.

“That’s going to really crank up the capability to around 16,000 kilograms (about 35,000 pounds) to low-Earth orbit, so that’s a doubling of the capability of the rocket that we’re currently flying,” Eberly said.

Firefly has said the medium-lift rocket it’s developing with Northrop Grumman “will evolve into a reusable vehicle” after initial flights as an expendable launcher.

This is not Northrop Grumman’s first foray into building a larger rocket than the Antares. Northrop abandoned a proposed rocket called OmegA in 2020 after it lost a lucrative military launch contract to ULA and SpaceX.