Seeing his words on the printed page is a big deal to Andrew Leland—as it is to all writers. But the sight of his thoughts in written form is much more precious to him than to most scribes. Leland is gradually losing his visiondue to a congenital condition called retinitis pigmentosa, which slowly kills off the rods and cones that are the eyes’ light receptors. There will come a point when the largest type, the faces of his loved ones, and even the sun in the sky won’t be visible to him. So, who better to have written the newly released book The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight, which presents a history of blindness that touches on events and advances in social, political, artistic, and technological realms? Leland has beautifully woven in the gleanings from three years of deteriorating sight. And, to his credit, he has done so without being the least bit doleful and self-pitying.

Leland says he began the book project as a thought experiment that would allow him to figure out how he could best manage the transition from the world of the sighted to the community of the blind and visually impaired. IEEE Spectrum spoke with him about the role technology has played in helping the visually impaired navigate the world around them and enjoy the written word as much as sighted people can.

IEEE Spectrum: What are the bread-and-butter technologies that most visually impaired people rely on for carrying out the activities of daily living?

Andrew Leland: It’s not electrons like I know you’re looking for, but the fundamental technology of blindness is the white cane. That is the first step of mobility and orientation for blind people.

It’s funny…. I’ve heard from blind technologists who will often be pitched new technology that’s like, “Oh, we came up with this laser cane and it’s got lidar sensors on it.” There are tools like that that are really useful for blind people. But I’ve heard super techy blind people say, ‘You know what? We don’t need a laser cane. We’re just as good with the ancient technology of a really long stick.”

That’s all you need. So, I would say that’s No. 1. No. 2 is about literacy. Braille is another old-school technology, but there’s of course, a modern version of it in the form of a refreshable Braille display.

How does the Braille display work?

Leland: So, if you imagine a Kindle, where you turn the page and all the electric Ink reconfigures itself into a new page of text. The Braille display does a similar thing. It’s got anywhere between like 14 and 80 cells. So, I guess I need to explain what a cell is. The way a Braille cell works is there’s as many as six dots arranged on a two-by-three grid. Depending on the permutation of those dots, that’s what the letter is. So, if it’s just a single dot in the upper left space , that’s the letter a. if it’s dots one and two—which appear in the top two spaces on the left column, that’s the letter b. And so, in a Braille cell on the refreshable Braille display there are little holes that are drilled in, and each cell is the size of a finger pad. When a line of text appears on the display, different configurations of little soft dots will pop up through the drilled holes. And then when you’re ready to scroll to the next line, you just hit a panning key and they all drop down and then pop back up in a new configuration.

They call it a Braille display because you can hook it up to a computer so that any text that’s appearing on the computer screen, and thus in the screen reader, you can read in Braille. That’s a really important feature for deafblind people, for example, who can’t use a screen reader with audio. They can do all of their computing through Braille.

And that brings up the third really important technology for blind people, which is the screen reader. It’s a piece of software that sits on your phone or computer and takes all of the text on the screen and turns it into synthetic speech—or in the example I just mentioned, text to Braille. These days, the speech is a good synthetic voice. Imagine the Siri voice or the Alexa voice; it’s like that, but rather than being an AI that you’re having a conversation with, it moves all the functionality of the computer from the mouse. If you think about the blind person, you know having a mouse isn’t very useful because they can’t see where the pointer is. The screen reader pulls the page navigation into the keyboard. You have a series of hot keys, so you can navigate around the screen. And wherever the focus of the screen reader is, it reads the text aloud in a synthetic voice.

So, if I’m going in my email, it might say, “112 messages.” And then I move the focus with the keyboard or with the touch screen on my phone with a swipe, and it’ll say “Message 1 from Willie Jones, sent 2 p.m.” Everything that a sighted person can see visually, you can hear aurally with a screen reader.

You rely a great deal on your screen reader. What would the effort of writing your book have been like with your present level of sightedness if you had been trying to do it in the technological world of, say, the 1990s?

Leland: That’s a good question. But I would maybe suggest pulling back even further and say, like, the 1960s. In the 1990s, screen readers were around. They weren’t as powerful as they are now. They were more expensive and harder to find. And I would have had to do a lot more work to find specialists who would install it on my computer for me. And I would probably need an external sound card that would run it rather than having a computer that already had a sound card in it that could handle all the speech synthesis.

There was screen-magnification software, which I also rely a lot on. I’m also really sensitive to glare, and black text on a white screen doesn’t really work for me anymore.

All that stuff was around by the 1990s. But if you had asked me that question in the 1960s or 70s, my answer would be completely different because then I might have had to write the book longhand with a really big magic marker and fill up hundreds of notebooks with giant print—basically making my own DIY 30-point font instead of having it on my computer.

Or I might have had to use a Braille typewriter. I’m so slow at Braille that I don’t know if I actually would have been able to write the book that way. Maybe I could have dictated it. Maybe I could have bought a really expensive reel-to-reel recorder—or if we’re talking 1980s, a cassette recorder—and recorded a verbal draft. I would then have to have that transcribed and hire someone to read the manuscript back to me as I made revisions. That’s not too different from what John Milton [the 17th-century English poet who wrote Paradise Lost] had to do. He was writing in an era even before Braille was invented, and he composed lines in his head overnight when he was all alone. In the morning, his daughters (or his cousin or friends) would come and, as he put it, they would “milk” him and take down dictation.

We don’t need a laser cane. We’re just as good with the ancient technology of a really long stick.

What were the important breakthroughs that made the screen reader you’re using now possible?

Leland: One really important one touches on the Moore’s Law phenomenon: the work done on optical character recognition, or OCR. There’s been versions of it stretching back shockingly far—even to the early 20th century, like the 1910s and 20s. They used a light-sensitive material—selenium—to create a device in the twenties called the optophone. The technique was known as musical print. In essence, it was the first scanner technology where you could take a piece of text and put it under the eye of a machine with this really sensitive material and it would convert the ink-based letter forms into sound.

I imagine there was no Siri or Alexa voice coming out of this machine you’re describing.

Leland: Not even close. Imagine the capital letter V. If you passed that under the machine’s eye, it would sound musical. You would hear the tones descend and then rise. The reader could say “Oh, okay. That was a V.” and they would listen for the tone combination signaling the next letter. Some blind people read entire books that way. But that’s extremely laborious and a strange and difficult way to read.

Researchers, engineers, and scientists were pushing this sort of proto–scanning technology forward and it really comes to a breakthrough, I think, with Ray Kurzweil in the 1970s when he invented the flatbed scanner and perfected this OCR technology that was nascent at the time. For the first time in history, a blind person could pull a book off the shelf—[not just what’s] printed in a specialized typeface designed in a [computer science] lab but any old book in the library. The Kurzweil Reading Machine that he developed was not instantaneous, but in the course of a couple minutes, converted text to synthetic speech. This was a real game changer for blind people, who, up until that point, had to rely on manual transcription into Braille. Blind college students would have to hire somebody to record books for them—first on a reel-to-reel then later on cassettes—if there wasn’t a special prerecorded audiobook.

Audrey Marquez, 12, listens to a taped voice from the Kurzweil Reading Machine in the early 1980s.Dave Buresh/The Denver Post/Getty Images

Audrey Marquez, 12, listens to a taped voice from the Kurzweil Reading Machine in the early 1980s.Dave Buresh/The Denver Post/Getty Images

So, with the Kurzweil Reading Machine, suddenly the entire world of print really starts to open up. Granted, at that time the machine cost like a quarter million dollars and wasn’t widely available, but Stevie Wonder bought one, and it started to appear in libraries at schools for the blind. Then, with a lot of the other technological advances of which Kurzweil himself was a popular kind of prophet, those machines became more efficient and smaller. To the point where now I can take my iPhone and snap a picture of a restaurant menu, and it’ll OCR that restaurant menu for me automatically.

So, what’s the next logical step in this progression?

Leland: Now you have ChatGPT machine vision, where I can hold up my phone’s camera and have it tell me what it’s seeing. There’s a visual interpreter app called Be My Eyes. The eponymous company that produced the app has partnered with Open AI, so now a blind person can hold their phone up to their refrigerator and say “What’s in this fridge?” and it’ll say “You have three-quarters of a 250 milliliter jug of orange juice that expires in two days; you have six bananas and two of them look rotten.”

So, that’s the sort of capsule version of the progression of machine vision and the power of machine vision for blind people.

What do you think or hope advances in AI will do next to make the world more navigable by people who can’t rely on their eyes?

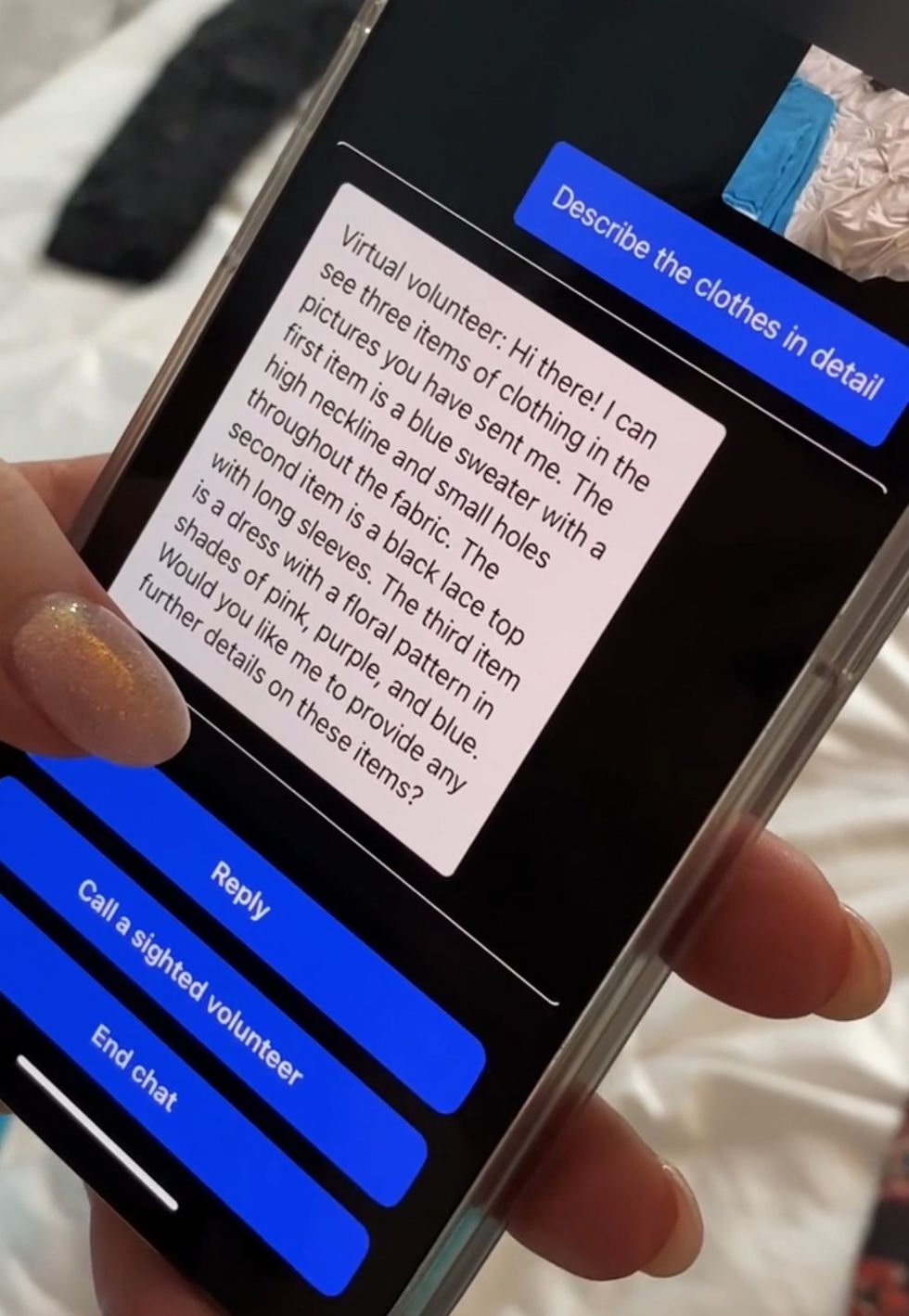

Virtual Volunteer uses Open AI’s GPT-4 technology.Be My Eyes

Virtual Volunteer uses Open AI’s GPT-4 technology.Be My Eyes

Leland: [The next big breakthrough will come from] AI machine vision like we see with the Be My Eyes Virtual Volunteer that uses Open AI’s GPT-4 technology. Right now, it’s only in beta and only available to a few blind people who have been serving as testers. But I’ve listened to a couple of demos that they posted on podcast, and to a person. They talk about it as an absolute watershed moment in history of technology for blind people.

Is this virtual interpreter scheme a totally new idea?

Leland: Yes and no. Visual interpreters have been available for a while. But the way Be My Eyes traditionally worked is, let’s say you’re a totally blind person, with no light perception and you want to know if your shirt matches your pants. You would use the app and it would connect you with a sighted volunteer who could then see what’s on your phone’s camera.

So, you hold the camera up, you stand in front of a mirror, and they say, “Oh, those are two different kinds of plaids. Maybe you should pick a different pair of pants.” That’s been amazing for blind people. I know a lot of people who love this app, because it’s super handy. For example, if you’re on an accessible website, but the screen reader’s not working [as intended] because the check out button isn’t labeled. So you just hear “Button button.” You don’t know how you’re going to check out. You can pull up Be My Eyes, hold your phone up to your screen, and the human volunteer will say “Okay, tab over to that third button. There you go. That’s the one you want.”

And the breakthrough that’s happened now is that Open AI and Be My Eyes have rolled out this technology called the Virtual Volunteer. Instead of having you connect with a human who says your shirt doesn’t match your pants, you now have GPT-4 machine vision AI, and it’s incredible. And you can do things like what happened in a demo I recently listened to. A blind guy had visited Disneyland with his family. Obviously, he couldn’t see the pictures, but with the iPhone’s image-recognition capabilities, he asked the phone to describe one of the images. It said, “Image may contain adults standing in front of a building.” Then GPT did it: “There are three adult men standing in front of Disney’s princess castle in Anaheim, California. All three of the men are wearing t-shirts that say blah blah.” And you can ask follow-up questions, like, “Did any of the men have mustaches?” or “Is there anything else in the background?” Getting a taste of GPT-4’s image-recognition capabilities, it’s easy to understand why blind people are so excited about it.